Tolstoy, Monet, and Meaning-making

When I was in the second grade, I had a brief but glorious stint in the talented and gifted program, something that went straight to my head. It was only for one year (was that Bush or was that me? I’ll never know) but one of the things I remember during this short tenure was my first acquaintance with Monet’s water lilies. We learned about impressionism and did our own impressionistic paintings copying The Water Lily Pond. I still have my sweet, blotchy attempt somewhere at my parent’s house tucked in some closet with all my other attempts at genius, artistic or otherwise. Between that and the copy of The Artists Garden at Giverny that hung in my bedroom, Monet has been my baseline for what art is. Like most Americans, I am perfectly calibrated to impressionism– it is modern enough to be engaging for my brain but not so abstract that beauty has been sacrificed in the pursuit of the novel and intellectual. Monet doesn’t ask much of me as a viewer, it is soft and warm and mostly flowers– what’s not to love? I was in Paris in May and naturally went to L’Orangerie to see the great water lily murals in person.

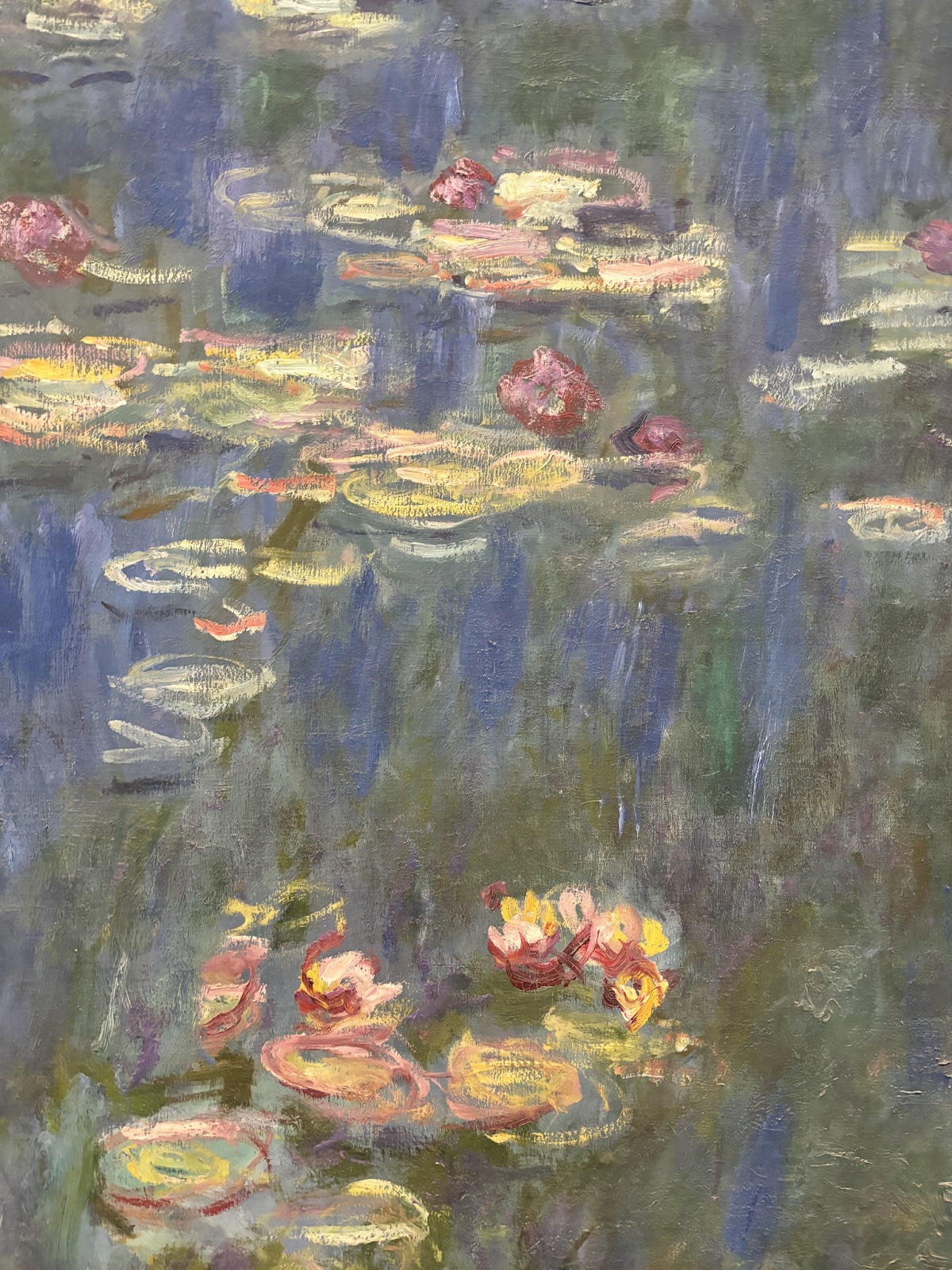

There were four paintings in two oval-shaped rooms, one canvas on each of the four sides– two long and two short. For each painting, I went through it up close and slowly— undoubtedly annoying those trying to take pictures. I was baffled by how much red, yellow, black, and brown emerged in the individual brush strokes of what far away looked blue. It was beautiful chaos, easy to mistake for meaninglessness. Occasionally, I would come across a cluster of strokes that looked like a flower and it would make my heart leap– I knew what that was! Then I would return to the murky obscurity, wading through black-green, black-purple, and black-brown. I don’t know how he managed it, but every single shade of blue and every thickness of paint was represented, making the surface as ripple-y as the subject matter. I started to find my own images– a cluster of brushstrokes that looked like a face, a dog, a tree– and then move along.

After going through it close up, I would step way back and try to take in the thing as a whole, ready for that Ferris Bueller’s Day Off magic. Far away, the brushstrokes blended– lightening and darkening into recognizable images– water, trees, water lilies, ripples in the water. The spell is lifted and you can SEE. Patches of darker colors became boundaries between objects— it is beautiful, the act of co-creation with the artist, your eyes doing the last job by blurring and blending colors, finding what can be identified. The way the room was set up, looking straight at the paintings, you couldn’t get the whole thing in your field of vision– sure you could focus on the middle and let your eyes blur the edges, but as far as my ability to look at the painting in its entirety, I was constrained by the limitations of my sight; I had to turn my head and in so doing, missed the other side. Seeing the whole image actually warped the image, it didn’t make it better. They aren’t meant to be seen all at once, they are meant to fill up your whole eye line. The longer I looked at the paintings, the more I realized that though the image did overall become clearer, it also remained elusive. Some of the paintings looked like maybe there were clouds reflected on rippled water but it was hard to tell. Others were obviously a depiction of dusk so the shapes were even more confusing, even with the added perspective. One was all yellow and I have no idea what that was– a reflection? It didn’t match the others compositionally and yet? Somehow it did. One of the people on the audio guide called these rooms the “Sistine Chapel of Impressionism” and described the paintings as “liberated” and that seemed right to me— there was something energetic and unbounded in the experience of viewing them.

It reminded me of War and Peace by Tolstoy. Covering 15 years of time during the Napoleonic Wars in Russia, it is famously very long (1000 pages, 600 characters, etc). Like my inability to see the water lilies, the novel resists any single viewing, any one-sitting read. Instead, you must turn your head, you must live alongside it and you must negotiate the fact that you cannot hold it all in your head at once. Maybe the other reason that these works reminded me of War and Peace is that it is a book filled with people who are trying to make and find meaning in their lives, despite the apparently meaningless actions of people totally out of their control (Napoleon). Pierre, Andrei, Natasha, Nikoli– these are people who want to be good— great even— but cannot live up to their ideals, nor shake off the narratives to which they subject themselves. Natasha wants a great love, Pierre wants to enact social change, Andrei wants to find meaning in this life. All of the struggles and conflict they face are complicated by the fact that they are aware of the stories that are happening to them and aware that those stories are shaping what and who they are. Their attempts at meaning making are sweet, and silly, and occasionally profound; just like ours.

We all do this which is one of the many reasons that I love Tolstoy so much– there is so much honesty. I suppose that some sort of cohesion of life– that the good and the bad, when given space and time– makes sense. That is ultimately the product pedaled by Christianity; that someone is painting our lives, or helping to write our stories, that experiences we have are not just meaningless strokes on some canvas floating on a rock, but that you are in the hands of an artist, and that when the painting is finished it will be beautiful and make sense. People (me) love to look back on their lives and mythologize them, we all want to be heroes in our journey. I never feel this pull as strongly as when I am in love or when I am in the early days of a crush– the storytelling of it is as powerful as the actual experience (incredibly Natasha coded), if not more, because, honestly, most of life feels pretty meaningless– do we ever have a good handle on what things mean? Can we ever perceive things outside the limits of our perspective? The way I storytell my own life is malleable and suggestable– I am often astonished at my ability to recontextualize and recategorize the memory of my own experiences, the power that they have in my life, and how those things form and change my understanding of myself. I love to observe how I tell the stories of my life to other people; the way they shift and change depending on the time that has passed, the things that I see with added information, the ways I was wrong– let alone the people and circumstances that populate the moment of telling. Regardless of the way I tell a story, the process of picking out from the colorful streaks of memory in order to make sense of them– it is all done with the assumption that there IS or at least SHOULD BE a meaningful story in the middle of it all. But there, looking at the water lilies, unable to see them in their entirety and understanding some of them even less, that whole process of storytelling felt contrived and silly– such arrogance, to assume we ever have a handle on it all.

And yet. In the presence of a painting I couldn’t even see and despite my best efforts resisted my intellectualization, and I didn’t feel hopeless. I felt small and grateful to be in the presence of something so big and whole, something that was so beautiful, so obviously the work of a master. My body would enter those rooms and exit them, and the water lilies would keep on water lilly-ing, the brushstrokes would continue to blend in the eyes of the beholder in that final act of participatory creation, and the stories of all of those who came and went would continue to be imagined and created by their minds. No matter what I had concocted The Water Lilies to mean would pale in comparison to the fact that they existed, I had seen them, and there was something beautiful and true in the moments they captured.

Leave a comment