I am now officially done with classes (devastating) and onto the summer schedule which is to be spent working on my dissertation— a 15,000 word essay about a topic of my choice. I am writing about Paradise Lost and the Book of Job (the one true academic love of my life) and how they explore the relationship between poetry and theology.1 I am extremely excited to start working on this— I have had these ideas floating around for years and the chance to sit down and flush them out/ think through them is exhilarating.

First! A brief reminder of the two works

In the opening section of Paradise Lost, Milton claims he is going to “justify the ways of God to men,” a bold claim, to say the least.

“Strategies of exegesis” means strategies of reading the bible, or how the bible is to be read. I have yet to answer my question (I need to read approximately 400 books before I can be sure), however my suspicion is that the whole attitude of the project of Paradise Lost is built around the book of Job→ Both are asking why we suffer and at whose hand. I think that Milton is teaching readers how to read the bible (what to ask, how closely to question the text, etc.) through the way he writes Paradise Lost. The theological issues that make readers uncomfortable in Paradise Lost are all present in the Book of Job. Both demonstrate the poet’s unique position (language and form) to respond to questions of theology by attuning the reader to God’s creation (human and non-human)– is the non-answer closer to truth?

In the next section I go through the big ideas of my three main chapters.

This section will start with an examination of the parallel relationships between the created questioning creator in the book of Job and of the created justifying creator in Paradise Lost. What do these works implicitly and explicitly teach the readers about questioning God? In both, there is evidence that God is both amenable and unhappy with the audacity of the created questioning creator. In this section, the focus will be on Adam’s relationship with God and the mixed messages he receives about God’s openness to being questioned in Paradise Lost. On the one hand, Adam’s queries are how Eve comes into being, on the other hand, Raphael is clear about the danger of seeking too much knowledge. In Job, a similar mixed message is received: Job is not instructed to repent, and God does respond, however his response only emphasizes how little Job can understand Him. In Paradise Lost the purpose is stated explicitly: to justify the ways of God to men. For God to need justification, it means that someone has come up with questions or grievances to lay at God’s feet. Here there is a clear dialog between Paradise Lost and the book of Job and Milton’s reading of the book of Job is manifest by how he treats questioning in Paradise Lost. How do these literary and poetic works address this question of theology? By not answering. The project of Paradise Lost is based on questioning and that Job is uniquely positioned to influence the way in which Milton contradicts himself.

This section will discuss how each work draws attention to the power the author wields over the reader’s experience– so much power that a reader is taken in by Satan, is brought face to face with their expectations as they are inverted, and is given a glimpse into omniscience. This authorial power over the reader is accomplished through the distinct poetic voice of the book of Job and Paradise Lost. Milton and the author of Job position themselves in the place of a god, controlling the text over which they have dominion.

One way is that each work inverts the expectations of the readers. Both start with the confusing relationship between God and Satan; Paradise Lost surprisingly starts in hell and Job surprisingly starts in heaven. This works to not only invert expectations but to attune the reader to the fact that they have assumptions in the first place, assumptions specifically about narrative and about God. The narrative aspect is crucial– these are stories told in poem form, not theological treatises.

Paradise Lost and Job are both written in a style that is meant to attune the reader to the fluidity of time: Paradise Lost is an epic and Job is a myth (or an epic). There is a timelessness to Job, a world that seems nearly without reference. In Paradise Lost, time is complicated– on the one hand, Milton’s material world is measured in definable units, on the other, the devils are defined by their future actions and ills and Christ is celebrated as if he has already accomplished the victory over sin and death. In both works, the reader is privy to knowledge that the actors are not, specifically knowledge about God. Readers of Paradise Lost know that Milton is bound to the biblical narrative, readers of Job know that the energy of the story is driven by a heavenly wager. How does knowing what will happen in the story change the story? That question becomes crucial when discussing God’s omniscience and human free will.

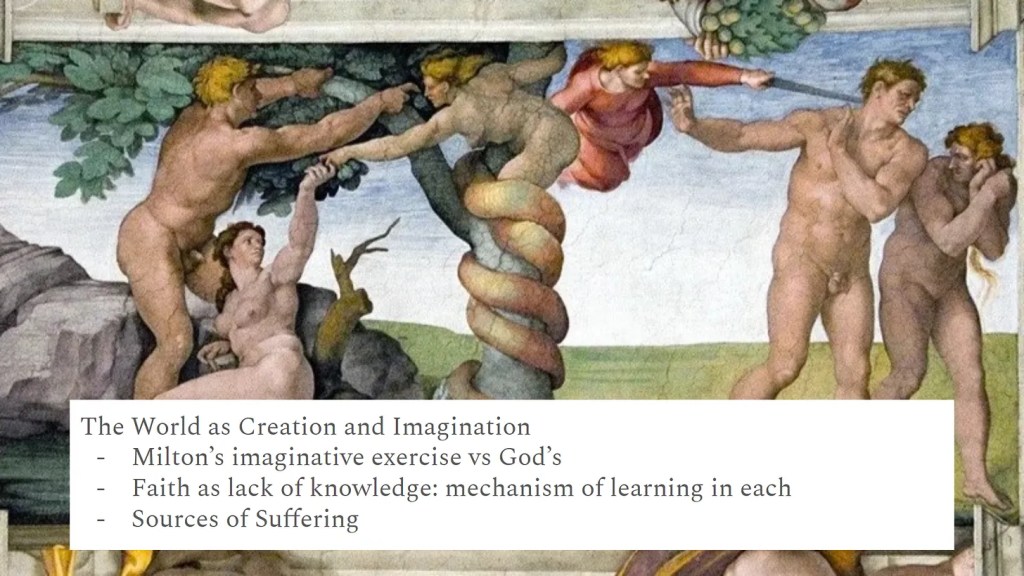

This section will trace the pattern of knowledge, suffering and imagination in both works. Knowledge and understanding are crucial in both texts, yet faith in God requires a lack of knowledge. In Paradise Lost, knowledge is linked to sin, but it is also the only way that Adam and Eve can resist sin. Suffering complicates the questions of knowledge. Both texts offer ambiguous readings as to God’s role in suffering and God’s attitude toward the sufferers. Both suggest that God is the cause of suffering– Job stating it outright. How do theology and poetics approach the problem of suffering? How is the role of the poet different from the role of the theologian? In the last section, there will be a comparison of the imaginative exercise that God is asking Job to participate in with the imaginative exercise that is the project of Paradise Lost. What role does imagination, specifically imagination tied to creation, have in understanding the relationship between God and man? How do these texts specifically position imagination and creation as literary non-answers to very real theological questions?

I am sure that this plan will modify itself as I go along— I have too many big ideas and not that much time to make my own modest argument. I can’t wait though!

Leave a comment